Wealth doesn't cause democracy, but development might

What revised modernization theory means for China

Why are some societies democratic and others not? Modernization theory is probably the most famous social-science account of transitions to democracy. The theory postulates that as societies economically develop and get richer, democratization becomes much more likely (even if not guaranteed). There are many plausible mechanisms on offer connecting income to democracy, such as education, changing norms (from materialism to post-materialism), urbanization, and so on. But whatever explains the correlation between development and democracy, the connection seems to be pretty real.

Well, no, not really. There’s been a lot of back-and-forth on the topic, with people corroborating and others challenging the correlation. Then, now almost a decade ago, a comprehensive meta-analysis of 33 studies and 492 estimates demonstrated that per capita income has no statistically significant, quantitatively meaningful effect on democracy, at least when the latter is understood as a non-binary, graded concept.

As always, I think findings like that should move us quite substantially. In lieu of strong additional considerations or new (better) quantitative evidence, we just have to accept that we cannot conclude development leads to democracy. I want the connection to exist both because it seems intuitive to me and because it offers hopeful, if tentative, predictions that as other societies become rich, they’ll mostly turn toward democracy. I’d love that, because I think liberal democracy is pretty neat and because I think Fukuyama is on to something (read my recent piece on his empirical vindication). It would be especially cool to see this in the case of China. In fact, largely based on modernization theory, many people in the 1990s forecasted just that – a prediction that sadly hasn’t turned out to be true even by 2025.

Additional considerations

Perhaps due to these biases of mine, I think more can and should be said about modernization theory, or at least a version of it, besides admitting that the meta-analytic result is unfortunately null.

A bunch of new-ish papers have resurrected a modified version of modernization theory by fundamentally reframing what matters about development. The key assumption is that it’s not GDP per capita that drives democratization, but the structural changes that development typically brings; particularly the capacity of ordinary people to disrupt the political and economic order. To the extent that GDP induces these structural changes, we should see (and have seen) a connection between riches and democracy. But because GDP is just an imperfect proxy, it shouldn’t be surprising that a simple correlation breaks down in many cases.

There’s a couple of arguments that break this general idea down.

One argument is that factory production, which arrives with development, requires large groups of workers to function together in highly specialized roles. Doing so

efficiently requires instilling manufacturing workers with a wide range of organizational and attitudinal capabilities that foster cooperation on a large and impersonal basis (e.g., negotiating and working together with strangers and dealing with disagreements, accepting authority, disciplining free riders).

These capabilities are clearly important for mass organization in general, which means that development/industrialization unintentionally increases ordinary people’s capacity to mobilize politically.

A related argument is that when workers are concentrated in specific industries, such as manufacturing, mining, construction, and transport, they’re much more capable of costly disruptions of the routines on which economic and political elites depend and to mobilize collective action. Thus, industrialization at the same time changes the calculus for autocratic elites. Because of the significantly greater forward and backward linkages in manufacturing and the other mentioned industries, economies that rely heavily on them are much more strongly disrupted by political instability than countries that do not. Additionally, repressing mass protests in highly industrialized countries is particularly expensive because, as intimated above, revolts tend to be more frequent, larger, better coordinated, and closer to urban centers of power.

In short, once the cost of repression rises sufficiently, autocratic elites are more likely to find it in their own best interest to allow democracy as it is cheaper than continuing political repression.

New evidence

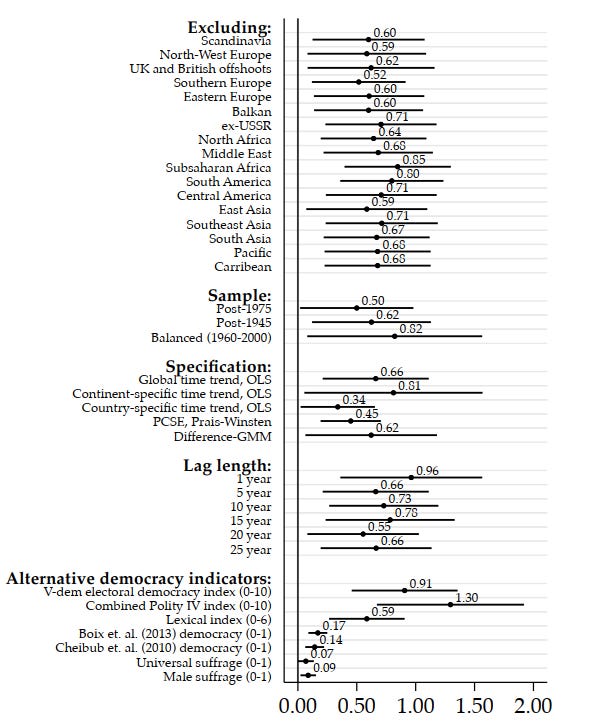

Using novel manufacturing employment data for 145 countries over 170 years, van Noort shows that industrialization strongly predicts democratization even after accounting for country and time fixed effects. The relationship is remarkably robust (see figure below, which depicts robustness checks) and significantly larger than the effect of GDP per capita, Gini inequality, average years of education, urbanization, as well as many other standard determinants of democracy.

As he notes, virtually all of today’s highly developed countries in the West and East Asia democratized shortly after reaching high shares of employment in manufacturing, and all democratized on levels of industrialization virtually unprecedented by any undemocratic country today or in the past. Yet many of these same countries democratized at levels of income, equality, education, and urbanization that remain relatively modest by today’s standards of many autocratic countries.

A rough heuristic is that you need at least around 25% of the workforce in manufacturing (not just industry in general but manufacturing specifically) before becoming robustly democratic. Present-day China is at around 21%!

Usmani finds much the same with a different measure of industrialization and in a similarly long and large sample size. Higher disruptive capacity predicts higher democracy scores (while landlord power, an indication of pre-modernity, depresses them). His specifications include country fixed effects, year dummies, and lagged outcomes; results remain strong at multi-year lags and when conditioning on GDP per capita.

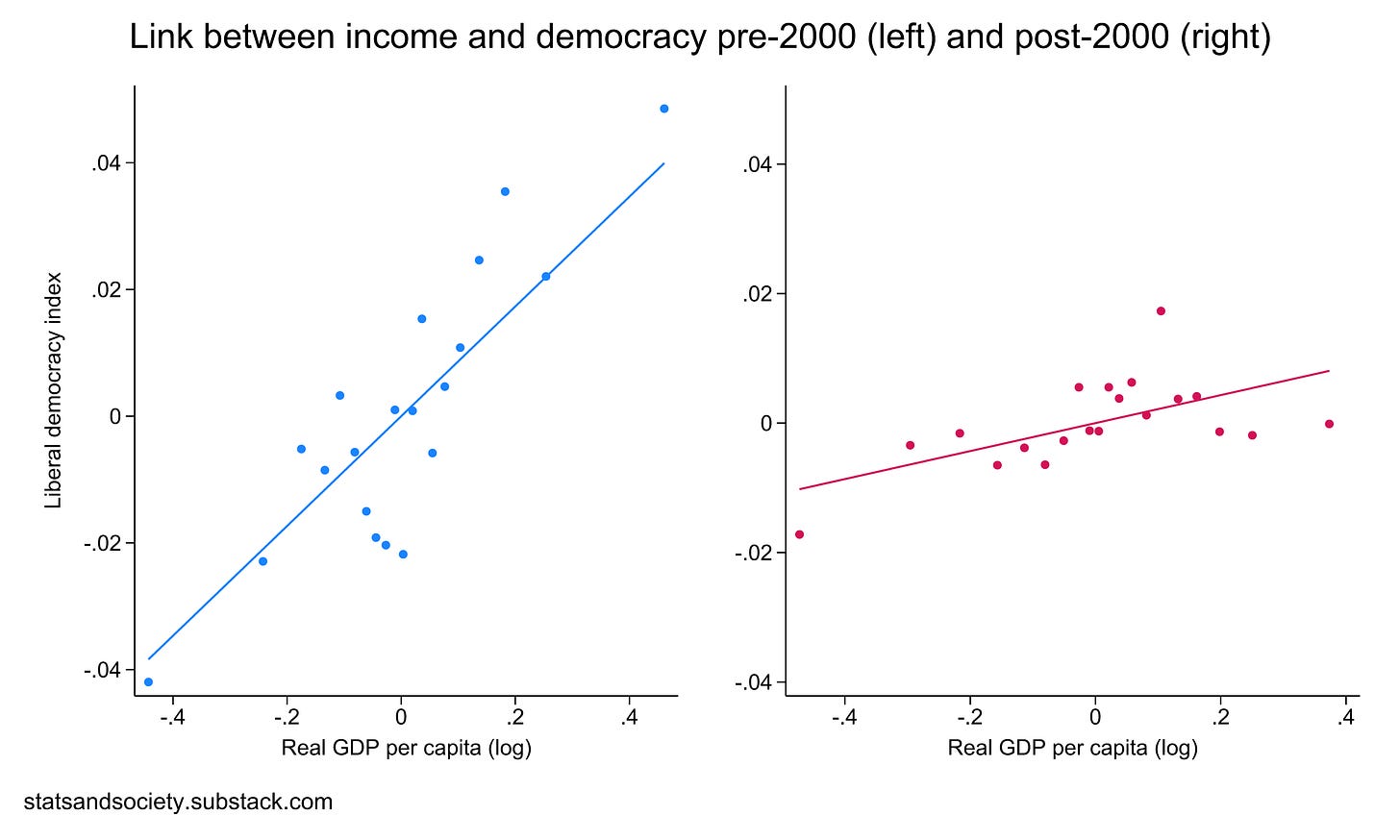

Tellingly, Usmani’s counterfactual exercises imply that roughly one-half to three-fifths of today’s democracy gap between developed and developing countries is explained by these capacity differences. In other words, in the past you had to go (and could go) far with manufacturing before becoming rich. Today, as countries step on the path to development, manufacturing peaks early, does so at a lower level, and starts declining sooner. So, development in the past robustly helped with democratization, because it helped so much with manufacturing. Today, the link between development and manufacturing is weaker, so the same level of development doesn’t translate to democratization as much as it did in the past.

Here’s a quick illustration of this idea that I cobbled together with a couple of decades of global data.

There’s another fairly recent and interesting paper (a large-scale sensitivity analysis of determinants of democracy) that comes to the same conclusion:

[O]ur results highlight uncertainty surrounding the relationship between income and democratization, but show that broader development processes enhance the chances of democratization. …

Until the last few decades, increasing income levels have corresponded strongly with changes in social structures (e.g., the rise of organized industrial workers and the middle class), which led to stronger pressures for democracy. With the growing automatization and digitization of production processes and market exchanges, however, a relatively small elite may now generate and accumulate considerable wealth; higher incomes thus may no longer correspond as strongly with social structural changes.

The conditional, lagged nature of modernization

Then there’s Daniel Treisman’s review article, which I think fits together quite nicely with these research papers. He argues that while a country’s income today provides little information about whether regime change will occur in the coming year, income is still strongly related to whether transition will occur during the next 20 years. That is, the relationship operates in the medium to long run, not the short run, which is consistent with the structural transformation point from before.

Treisman proposes what he calls “conditional” modernization theory to reconcile these patterns. The idea is that economic development creates only a predisposition toward democracy and does so only when it’s had time to affect structural social change (like manufacturing/disruptive capacity/lack of landlords). Some additional factor is then required to trigger actual regime change, and such triggering factors occur only intermittently. These triggers might include economic crises, military defeats, or leader turnover – whatever disrupts existing coordination schemes and open possibilities for regime change.

This can explain why we see waves of democratization. When international shocks (like global recessions or world wars) cause triggers to fire simultaneously across multiple autocracies, we see concentrated bursts of democratization among countries that have structurally modernized. It also makes it more understandable why a simple GDP-democracy link can be so fragile, depending on the time-period under investigation and the lags employed in regressions.

Back to China

The revised theory carries sobering implications for authoritarian modernization. With the exception of Japan, China is actually somewhat less industrialized than all of today’s highly developed countries were when they democratized. China’s manufacturing employment remains below the threshold where democracy becomes nearly inevitable in van Noort’s analysis. So, it shouldn’t be surprising that it remains undemocratic.

However, if it keeps developing, it might reach the critical level of manufacturing that’s seemingly needed. Or it might start economically slowing down, or simply continue developing without pushing manufacturing further, which would lower the chances of democracy emerging.

Whatever the case may be, and despite inconclusive findings regarding the income-democracy link, I think development might still be a key determinant of democratization, though only indirectly so. The conduit of manufacturing and disruptive capacity is crucial, though precisely for this reason development today is less predictive of democratization than it was in the past.

A few years ago, I came across The Dictator’s Handbook. Nothing I’ve read since explains more clearly what actually sustains egalitarian — and yes, democratic — societies.

If I try to summarise it from memory: it all comes down to the size of the winning coalition.

The more people a government truly depends on to stay in power, the more it is forced to provide broad public goods instead of narrow patronage. Large coalitions create democratic behaviour, even when the actors themselves aren’t democrats.

The opposite extreme is a system where you only need the loyalty of a tiny group — the military, the security services, a handful of oligarchs. In such systems, repression and selective rewards are simply the rational strategy.

I’ve learned so much new information here -- thanks for sharing this piece! :)

What do you think Hungary’s case means for our understanding of modernization theory (both the old and newer versions)? Why could Hungary backslide into electoral autocracy, despite being relatively more democratic in the 2000s, while other similar post-socialist countries, such as Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Croatia, or even Romania (countries with similar GDP per capita as Hungary), have remained more democratic and “free” according to Freedom House? This really makes me think!

To complicate things further: Hungary had a more liberal communist regime compared to other countries of the former Eastern Bloc. Romania and Czechoslovakia were notoriously autocratic. So Hungarian civil society -- although still more restricted than in Western societies -- was likely somewhat more developed during Hungary’s transition to democracy, yet we still observe backsliding.

What do you think? :D